Rick Wicklin simulates playing craps with unfair dice.

StubHub has a data blog. The first post examines the correlations between preference in sport (baseball vs. football) and political party (Democratic vs. Republican).

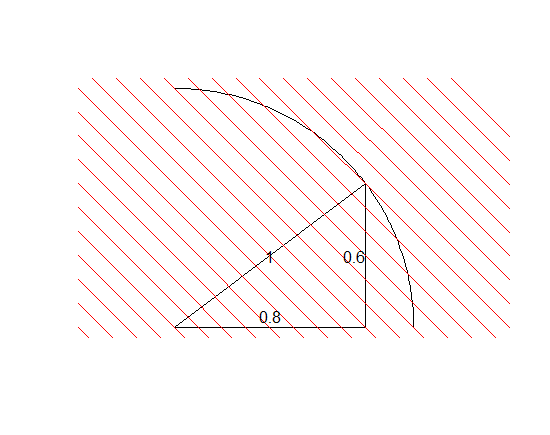

Integrals don’t have anything to do within discrete math, do they?. By Mark Kayll, winner of the MAA’s Allendoerfer prize for articles published in Mathematics Magazine.

Allen Downey has a rough draft of his book Think Bayes.

Steven Strogatz has written a brief, nontechnical introduction to catastrophe theory for the New York Times.

Probability and game theory in The Hunger Games.

Daniel Engber asks how the Internet fell in love with a stats class cliche. (You know which one.)

Shapley’s layman’s account of the general principles of game theory. (Was anyone else surprised, when the Nobel was announced, to learn that Shapley was still alive?)

The Daily Show with Nate Silver.

Brian Hayes writes about sphere packing for American Scientist and talks about how he made the images for his blog.

David Barber has written a textbook, freely available online, entitled Bayesian reasoning and machine learning.