James Tanton asked on Twitter:

As there are “more” triang nmbrs than sq nmbrs http://www.jamestanton.com/?p=1009 let f(N) = nmbr triangs >= N^2 but < (N+1)^2. Curious:What graph like?

The  th triangular number is about

th triangular number is about  (more precisely, it’s

(more precisely, it’s  .) So there are about

.) So there are about  triangular numbers less than

triangular numbers less than  . Therefore, “on average”, in each interval

. Therefore, “on average”, in each interval  there are

there are  triangular numbers.

triangular numbers.

For example, in the interval [9, 16) there are two triangular numbers, namely 10 and 15; this is f(3). In the interval [16, 25) there is one triangular number, namely 21; this is f(4).

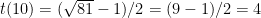

Let’s write down an explicit formula for f(n). Let g(x) be the number of triangular numbers less than x. To figure this out, I’ll introduce a function t(x), which takes as input x and outputs the index of x in the triangular-number sequence. For example, t(10) = 4, t(15) = 5. But we also want to be able to compute, say, t(12). But that’s fine! t(n) is just the inverse of the function which takes n to the nth triangular number, the function  ; in particular, solving the quadratic,

; in particular, solving the quadratic,

So  ;

;  .

.

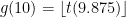

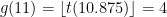

Next we write g(x) in terms of t(x). It’s tempting to say that g(x) = \lfloor t(x) \rfloor, but it’s not. t(10) = 4, for example, but we want g(10) = 3. We’ll say that  — we’ll only need this formula to work when x is an integer. So, for example,

— we’ll only need this formula to work when x is an integer. So, for example,  , and the index of 9.875 in the triangular number sequence, whatever that means, is between 3 and 4. But

, and the index of 9.875 in the triangular number sequence, whatever that means, is between 3 and 4. But  .

.

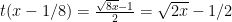

Why the constant 1/8? Because

which makes the formula marginally easier to write.

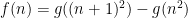

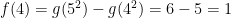

Finally  . Take the number of triangular numbers less than

. Take the number of triangular numbers less than  , and subtract the number less than

, and subtract the number less than  , and you get the number in the interval in between. For example

, and you get the number in the interval in between. For example  ; there are 6 triangular numbers less than 25, namely 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, and 21. And

; there are 6 triangular numbers less than 25, namely 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, and 21. And  . Thus

. Thus  , indicating the triangular number 21. So at long last we have the formula

, indicating the triangular number 21. So at long last we have the formula

.

.

In particular the arguments of these two floor functions differ by  , which is between 1 or 2, so f(n) is always either 1 or 2. The graph that Tanton asked about is below.

, which is between 1 or 2, so f(n) is always either 1 or 2. The graph that Tanton asked about is below.

You can see some hints of periodicity in the function; for example, from a quick glance at the graph it might look like  has period 12, each period containing five 2s and seven 1s. But this can’t hold, not unless

has period 12, each period containing five 2s and seven 1s. But this can’t hold, not unless  . In fact

. In fact  can’t be periodic, because

can’t be periodic, because  is irrational.

is irrational.