Today PNC Wealth Management announced its Christmas Price Index. This is the cost of buying all the gifts in the song The Twelve Days of Christmas. All 364 of them.

Where’d that number come from? Well, there is one on the first day: a partridge in a pear tree. There are three gifts on the second day: two turtle doves, and a partridge in a pear tree. And so on up until 78 gifts on the twelfth day: twelve drummers drumming, eleven pipers piping, and all the way on down. The total number of gifts bought is 1 + 3 + 6 + … + 78 = 364, which is, coincidentally, one less than the number of days in the year. (The number 365, being just the nearest integer to a ratio of two times, can’t have any number-theoretic significance.)

But what if Christmas lasted n days instead of three? What then?

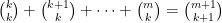

The identity  is a special case of

is a special case of

$

$

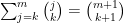

which in turn is a special case of the “hockey-stick identity”

$

$

or in more compact notation

.

.

Let’s prove this identity. We want to choose  elements from the set

elements from the set  . We can do this by first choosing the largest element, and then choosing the $k$ smaller elements. If we choose

. We can do this by first choosing the largest element, and then choosing the $k$ smaller elements. If we choose  to be the largest element, there will be

to be the largest element, there will be  ways to pick the

ways to pick the  smaller elements from

smaller elements from  ; summing over the possible values of

; summing over the possible values of  gives the answer.

gives the answer.

But a different way of counting is suggested by observing that over the 364 days, the true love receives:

partridges-in-pair-trees;

partridges-in-pair-trees; turtle doves;

turtle doves; french hens;

french hens;- …

drummers drumming

drummers drumming

and so we get the identity

.

.

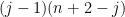

If there’s anything right with the world, this ought to be a special case of

and why should this be? Let’s write this as

where the reason for the somewhat strange indexing will be apparent shortly.

Let’s count subsets of the set  of size 3. We can write each such subset as

of size 3. We can write each such subset as  where we require

where we require  . > Then we’ll count these subsets according to the difference

. > Then we’ll count these subsets according to the difference  . To construct such a set with

. To construct such a set with  we must:

we must:

- choose

.

.  must be between

must be between  and

and  inclusive, so there are

inclusive, so there are  possible choices.

possible choices.

- choose

.

.  must be between

must be between  and

and  exclusive, so there are

exclusive, so there are  possible choices.

possible choices.

At this point  is fixed. So there are

is fixed. So there are  ways to choose the 3-set with

ways to choose the 3-set with  ; summing over the possible values of

; summing over the possible values of  gives the answer.

gives the answer.

(Is there a natural generaliztion of this later identity that counts sets of sizes 4 or larger?)

So by counting sets of size 3 in two different ways, we’ve made combinatorial proofs of two different identities, both with a binomial coefficient with “lower number” 3.

The 364-gift total has been observed in various places; people who have looked at the math instead of just adding up the numbers include Murray Bourne and Brent Yorgey. And Knuth observed that the song itself has a space complexity of  .

.