I recently read Magical Mathematics, by Persi Diaconis and Ron Graham. I am not a magician, so I’m not really qualified to comment on the magic. But these are two first-rate mathematicians and there are some nice little bits of mathematics in here. Here’s one of them.

At one point (pp. 124-125) they discuss the I Ching. Diviniation from this book requires constructing, essentially, a sequence of six bits; this enables one to pick out one of 26, or 64, “hexagrams”. Each hexagram has some associated text; that text is supposed to be interpreted as a commentary on the answer. (How far we have fallen! Now we have the magic 8-ball. And, I suppose, fortune cookies.) It’s traditional to represent each bit by either a broken line or a solid line, and furthermore to call those lines “changing” or “unchanging” — so there are really four possibilities:

- broken changes to solid (associated with the number 6)

- solid stays solid (associated with the number 7)

- broken stays broken (associated with the number 8)

- solid changes to broken (associated with the number 9

What is wanted is a way to pick one of these four possibilities at random.

One classical method for generating a random hexagram works as follows: begin with 49 sticks. Divide them into two piles at random. Set one stick aside; divide the remaining sticks into two piles. From each pile, count off the sticks in groups of four; add the last (possibly incomplete) group the one stick that was set aside.

You end up with a pile of either five or nine sticks — the two large piles had forty-eight sticks, and the groups other than the last contain some multiple of four. So the two last piles together contain a multiple of four sticks, either four or eight.

You now have either forty or forty-four sticks; repeat the whole procedure, setting one aside and breaking up into groups. You’ll end up with either four or eight sticks. Remove these, and repeat again; you’ll get a pile of either four or eight sticks.

So you have three small piles: one containing five or nine sticks, two each containing four or eight. Call a pile of size eight or nine “large”, and a pile of size four or five “small”; for each small pile score 3, for each large pile score 2. The sum of these three scores is 6, 7, 8, or 9, which gives the desired two bits.

There are other methods, often based on flipping coins; many of the more modern ones are criticized for not having the same probability distribution as this “classical” method. It’s not hard to come up with a method that gives half broken and half solid; but getting the “right” frequency of changing lines of each type is trickier.

Surprisingly, Diaconis and Graham just give the probabilities of getting 6, 7, 8, or 9, but don’t show how to compute them. (I say this is “surprising” because there seemed to be an indication that these probabilities would be given at the end of the chapter. So I want to briefly indicate how they’d be computed.

Let’s consider the first splitting. We take a pile of 48 and split it into a left-hand pile and a right-hand pile. The left-hand pile, we assume, is equally likely to have a number of sticks of the form  or

or  , leaving 1, 2, 3, or 4 sticks to be set aside respectively. In these cases the right-hand pile will have 3, 2, 1, or 4 sticks. So one-fourth of the time we set aside a large pile, and the rest of the time we get a small pile.

, leaving 1, 2, 3, or 4 sticks to be set aside respectively. In these cases the right-hand pile will have 3, 2, 1, or 4 sticks. So one-fourth of the time we set aside a large pile, and the rest of the time we get a small pile.

In each of the second and third splittings we start with a number of sticks which is a multiple of four; remove one stick; then go through the splitting process. Here, if the left-hand pile has 1, 2, 3, or 4 sticks in its final group then the right-hand pile will have 2, 1, 4, or 3 sticks in its final group; no matter what happens we must end up with three more than a multiple of four. So half the time we set aside a large pile, and half the time we set aside a small pile.

So we get a small pile on the first splitting with probability  , and on each of the later splittings with probability

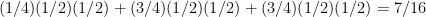

, and on each of the later splittings with probability  . The probability that there are three small piles is

. The probability that there are three small piles is  ; that there are two small piles is

; that there are two small piles is  ; that there is one small pile is

; that there is one small pile is  ; and that there is no small pile is

; and that there is no small pile is  .

.

The interesting thing to me is that if you only care about the parity of the number of small piles — that is, the initial broken-solid distinction — then there’s a lot of “extra” randomness here. You could just take the results of a single splitting, starting with a pile with size a multiple of four, and use that to get a bit which is equally likely to be broken or solid. In fact if we flip any number of (independent!) possibly biased coins, as long as there is at least one fair coin we’re equally likely to get an odd number or an even number of heads. But psychologically, perhaps people want to see multiple steps in the process – it gives the sense that the result is somehow “more random”.