Service on Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) runs every fifteen minutes on each route; every twenty minutes on evenings and Sundays. Here’s a map of the system. (The lines in red and green don’t run all the time, but that’s not relevant for what I’m about to say.)

The San Francisco city segment (Daly City to Embarcadero) is served by four of the five routes, and so has service by sixteen trains an hour when all those lines are running, between about 6 AM and 7 PM. Here’s a schedule. If you’re standing at, say, 16th Street (which I was a couple hours ago), northbound (Embarcadero-bound) trains depart at

6:11 am (red, i. e. Richmond-bound)

6:17 am (blue, i. e. Dublin-bound)

6:19 am (yellow, i. e. Pittsburg-bound)

6:24 am (green, i. e. Fremont-bound)

and then that pattern repeats every fifteen minutes through 4:11 pm. (Things get complicated slightly by extra trains in the Pittsburg direction in the evening rush.) That is, in a typical hour:

Dublin trains depart at 2, 17, 32, and 47 after the hour;

Pittsburg trains depart at 4, 19, 34, and 49 after the hour, that is, 2 minutes after the Dublin trains;

Fremont trains depart at 9, 24, 39, and 54 after the hour, that is, 5 minutes after the Pittsburg trains;

Richmond trains depart at 11, 26, 41, and 56 after the hour, that is, 2 minutes after the Fremont trains

(and of course Dublin trains depart 6 minutes after the Richmond trains).

(After that there are some extra trains in the direction of Pittsburg/Bay Point for the evening rush hour.)

You’ll notice that these trains are not evenly spaced.

So say I show up at 16th Street at a time chosen uniformly at random between, say, 2 PM and 3 PM, and I want to go to Embarcadero; what is my expected waiting time?

With probability 6/15, the next train heading in that direction is a Dublin train. In these cases, on average I will have to wait 6/2 = 3 minutes.

With probability 2/15, the next train heading in that direction is a Pittsburg train. In these cases, on average I will have to wait 2/2 = 1 minute.

With probability 5/15, the next train heading in that direction is a Fremont train. In these cases, on average I will have to wait 5/2 = 2.5 minutes.

With probability 2/15, the next train heading in that direction is a Richmond train. In these cases, on average I will have to wait 2/2 = 1 minute.

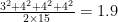

So my average waiting time is (6/15)(3) + (2/15)(1) + (5/15)(2.5) + (2/15)(1) = 2.3 minutes. You could also write this as

and this is an example of a general formula; the numerator is the sum of the squares of the times between different trains, the denominator is twice the period on which the system runs. On average I’ll have to wait 2 minutes and 18 seconds for a train if I just show up without looking at the schedule.

How much worse is this than the optimal spacing? The denominator of that fraction has to be 30; the numerator is the sum of the squares of four numbers that add up to 15. To minimize that sum of squares we want the numbers in the numerator to be as close together as possible. (This is roughly Jensen’s inequality.) Assuming that the inter-train spacings have to be integer numbers of minutes, we’ll go with 3, 4, 4, and 4, and the average wait time ends up being

and if we were allowed to not have the spacings be integer numbers of minutes, we could get this down to 1.875 minutes by having trains exactly three minutes and 45 seconds apart.

So BART is costing people who commute within San Francisco 0.425 minutes — or twenty-five and a half seconds — every morning and evening, with this non-optimal train spacing! Or fifty-one whole seconds a day! I suppose this isn’t really worth worrying about, especially since I spent a good half-hour writing this post…

(I haven’t thought hard enough to figure out if there’s some constraint that makes it impossible to space out trains more evenly; in particular that might interact poorly with the spacing on some other interlined segment of the network. It is also possible that this is deliberately done by BART so that people who just show up without looking at a schedule, intending to take the next train to a point within the city, are more likely to end up on Dublin or Fremont trains, as those are the lines that are less used in their East Bay segments; you can see that from this chart of number of people exiting at each station on weekdays and some artihmetic. If so, well done, BART people! If not, well, pretend you meant to do it that way.)

I’m looking for a job, in the SF Bay Area. See my linkedin profile.